How We Understand the Ancient History of Japan through the manipulation of “History”.

When did human history start?

It is a simple question, but one that is probably hard to answer. “History” started in Greece or China sometime around 4000 years ago, but there were only hunter-gatherers in most of the parts of Earth. When Columbus “discovered” the American continent, indigenous people were already there, and had constructed magnificent cities with pyramids. In this kind of context, why are hunter-gatherers and native Americans not included in history?

“What is history” is one of the most challenging questions, even for historians. One simple answer would be that history is a “written” thing. When something is written, not drawn or painted, with letters and characters, it can be considered as “history”, or historical records at least. Some remains are from ten thousand old or more, but since they are not written, paintings or artefacts, we consider the age as “primitive” or “prehistory”(先史). Although if we consider that history is things that have been written down, another question occurs: if we have no idea how to read or interpret some types of writing, such as some forms of cuneiform, then are they historical records?

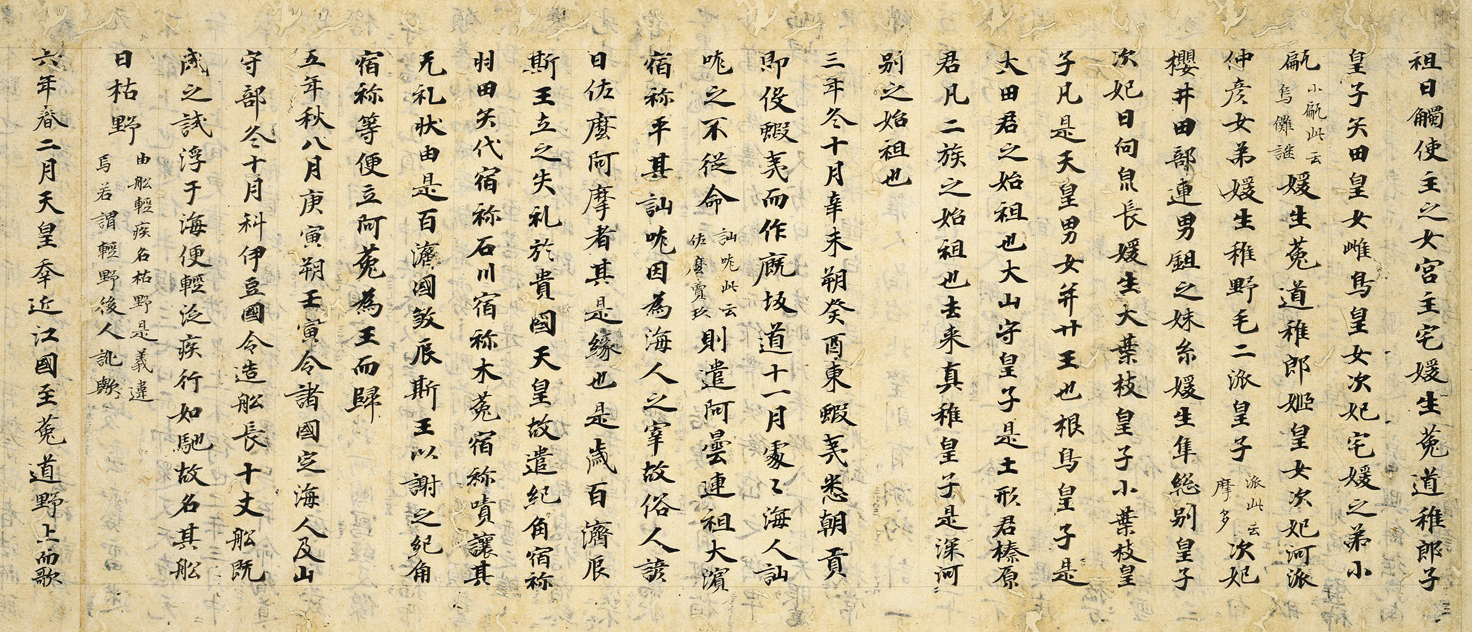

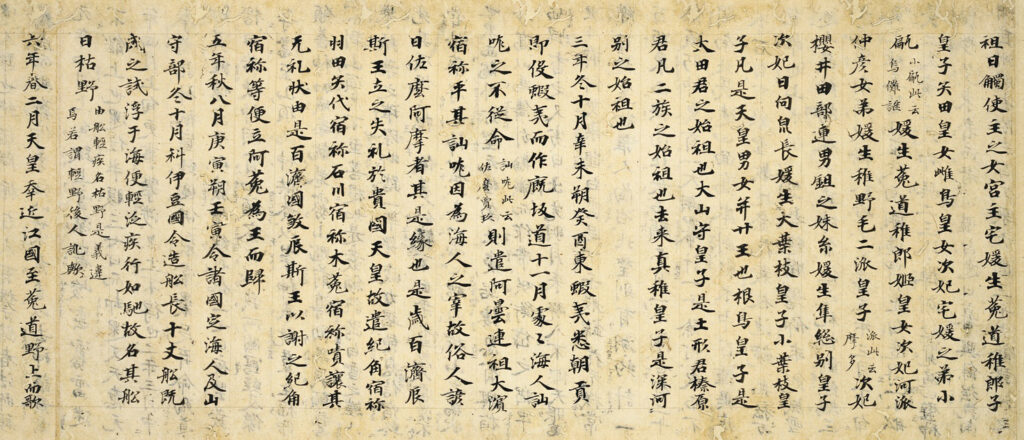

When we try to learn the history of Japan, textbooks usually tell us that the three oldest books in Japanese history are Kojiki (古事記), Nihon-Shoki (日本書紀) and Manyōshū (万葉集). Most of the historical details until the 7th century rely on these three.

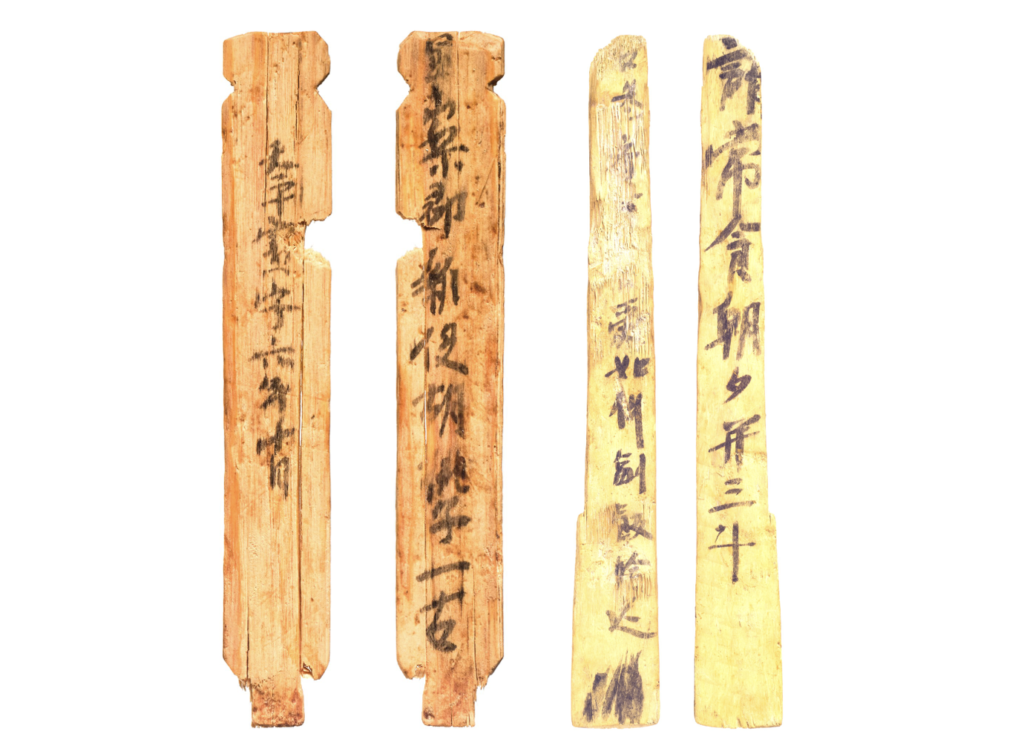

Source: ColBase (https://colbase.nich.go.jp)

There are older historical records, such as the characters written on the surface of iron swords (鉄剣) or wooden tablets (Mokkan, 木簡), but we barely have any historical details before these three books. Some ancient Chinese books also mention “Japan”, but they are not detailed or precise. 1

Kojiki and Nihon-shoki are history books; it is interesting that two of the oldest extant books in Japan fall into this category. We can assume they represent an attempt by humankind to retain history.

Manyōshū is the oldest collection of waka (和歌), traditional Japanese poetry. It seems as though ancient people tried to retain waka as well as history, and they succeeded: we still produce waka in the same form in modern times. (I wrote quite a few waka as mandatory assignments from elementary school onwards).

Kiki – Two different history books

You might wonder why there are two “oldest” history books. Both books were said to be compiled by Yamato-Tyōtei (大和朝廷), the ancient Imperial government based in present-day Nara prefecture. Yamato was the strongest kingdom in ancient Japan, and the bloodline of Yamato-Tyōtei leaders extends to today’s Imperial family.

Both Kojiki and Nihon-Shoki tell the earliest history of Japan. Since they feature the history of the same period, the Japanese call them “Kiki(記紀)”, a contraction of “Kojiki and Nihonshoki”. 2 This contraction is used formally, books and monographs written by historians. Yamato leaders intentionally wanted two types of history book, as will be explained below.

What is Kojiki?

Kojiki tells Japanese history from the very beginning, the Japanese version of Genesis, until the early 7th century. Kojiki is written as a series of stories, having scenes and dialogue, focusing on Gods and emperors; it does not simply enumerate the incidents in chronological order.

Kojiki is separated into three parts: the first part is full of exciting and meaningful stories of Gods and people; the second part describes how the first to 15th Emperors started reigning the lands of Japan; and the third part covers the 16th to 33rd Emperors and Empresses.

What is Nihon-Shoki?

The 40th Emperor ordered the preparation of Nihon-shoki to compile the whole history of Japan up until his time. Chokusen (勅撰) is the specific word for “compilation for the Emperor”, and chokusen history books are considered “true history(正史)” in Japan. Thus, Nihon-Shoki was supposed to be “true history”.

Nihon-Shoki tells the history of the first emperor until the 41st empress in chronological order3; you will probably find it more boring than Kojiki. Nihon-Shoki is often translated as “The Nihongi” in English: as a native Japanese, I find “Nigongi” very weird since 99% of Japanese people would not recognise both indicate the same book.

Why two history books?

Kojiki is very well told as a series of stories, and is fun to read. Imagine something like the Japanese version of Greek myths: there are gods of the sun and agriculture etc. Gods are interacting with each other and humans. Kojiki was written for people living on the Japanese islands so that they could have ideas about the history of the lands they live in. The first part of Kojiki is mythology, but at that time there was no distinction between myths and history.

On the contrary, Nihon-Shoki was compiled for those living in foreign countries. Yamato was trying to establish a decent position in East Asia, and having a magnificent history mattered. Hence, Nihon-Shoki was written in Chinese. We can, therefore, simply conclude that Kojiki was Japan’s history intended to prevail domestically, while Nihon-Shoki was internationally told Japan’s histoy.

Multiple tribes constituted “Japan”

The “Japanese” are often considered to be one unified tribe; many Japanese people themselves aslo think they are. But this is not true: ancient Japan consisted of multiple tribes and clans, as proven through recent studies of mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes. Some people came from China and Korea, some from the north, and another wave of people arrived from the Pacific Ocean.

Since there were multiple tribes, it is not hard to assume that battles and conflicts occurred among them. Therefore, Yamato kings needed strong mythology that could give them authority to rule them all. In Kojiki the Yamato kings are the descendants of the gods, which convince people that they have the authority to rule all the people in Japan because the Japanese version of Genesis says the gods gave birth to the Japanese islands.

However, for tribes other than Yamato being the descendants of pagan gods meant nothing. Hence, the Yamato government “borrowed” myths from multiple tribes and combined them all together in Kojiki, making it sound that as if they were actually all Yamato myths, and that all the people needed to obey the Yamato Kings.

Kojiki’s importance in comparative mythology

At the very beginning of Kojiki is the Japanese version of Genesis. There is no distinction between sky and land, just liquid. When the upper world called Takaamanohara (高天の原) separated from the “under world”, five genderless gods came into being in the upper world; gods with defined sex followed them.

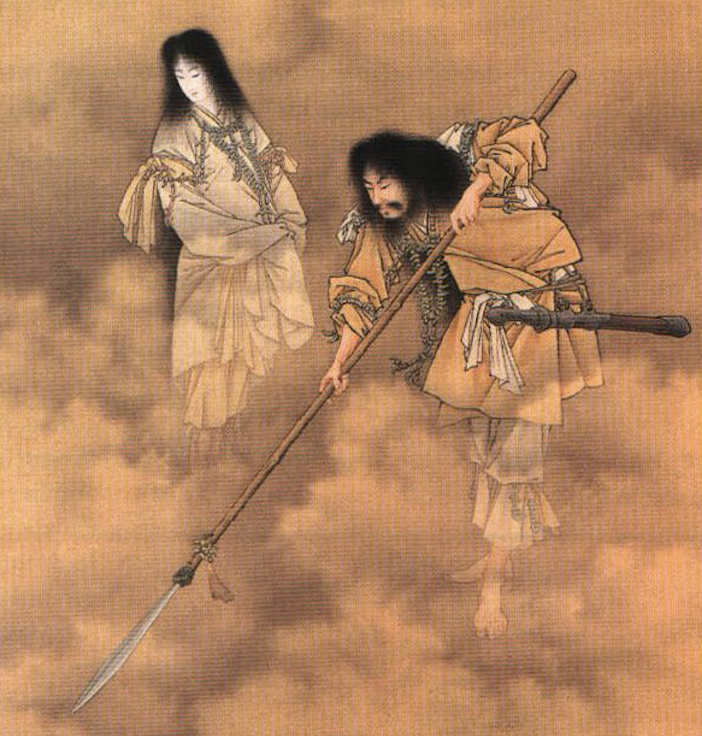

The god Isanagi and the goddess Izanami, brother and sister, go down to the under world. They stir the liquid with a fish spear, and a small island is made. There the two become husband and wife, they make love, and the goddess gives birth to everything, including the lands and islands of Japan and the gods of everything in the universe.

However, when Izanami gives birth to a god of fire, he burns his mother, causing her death. Izanagi feels tremendous grief, and he kills his baby god and goes to “the land of the dead” (黄泉の国), trying to bring his wife back. Izanagi finds Izanami, but she instantly hides and says that she cannot simply go back to the land of the living because she has eaten the food in the dead land. But she will negotiate with the god of the dead land, and asks Izanagi not to look at her until she has finished those dealings. However, he cannot help looking at her, and he sees his wife’s body rotting and falling apart.

Izanagi gets scared and run, while Izanami chases after him, getting very ashamed and angry at her husband. Finally reaching the land of the living, he blocks the road to the dead land with a huge stone, so that his wife cannot pass through. Izanami curses Izanagi saying: “Dearest husband, if thou do like this, I will in one day strangle to death a thousand of the folks of thy land.” Then, Izanagi replies: “My love, I will in one day set up a thousand and five hundred birthing-houses.” That is why people need to die and many more are born.

If you are of European descent, you probably recognised a few similarities to the Greek Myths. For example, Persephone could not go back to the living world because she had eaten pomegranate seeds. Also, “Do not look at me” is quite similar to the story of Orpheus going to the land of Hades to bring his beloved wife back. The Do-not-look-at-me taboo is found in myths and folklores in all corners of the world, including the Bible. Mythologists assume that a wave of people carried the story and spread it as far as Japan, at the limits of Eurasia.

Also, at the beginning of the story of Izanagi and Izanami, they stir the liquid with a fish spear. This can be related to Polynesian myths that are prevalent from Hawaii to the aboriginal tribe of New Zealand, the Maori.

The imperial family frequently claim that their ancestor god is especially the god of the Sun (天照大神) in Kojiki, which is the same concept as the Pharaohs of ancient Egypt. There are many other similarities between Japanese myths and African myths.

Greek myths and Roman myths are quite similar, and the reason for that can be established very easily. However, Kojiki also contains a large number of similarities to traditional stories from all over the world. Historians assume it is because Japan is the very edge of Eurasia, and many tribes of Homo Sapiens had independently reached Japan at a pretty early stage and then coexisted. If this suggestion were only supported by the similarity in mythology, it might just be a hypothesis, but its likelihood is strengthened by the results of the research using mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes.

Nihon-Shoki is fraudulent

Now you understand the intention of the Yamato government in trying to manipulate the Japanese people and their history through Kojiki. Compared with Kojiki, Nihon-Shoki tells the respectable and rational history of Japan: it is not too much to say that Nihon-Shoki is the one and only solid historical record of Japan until the 7th century. However, Nihon-Shoki also tells made-up history.

Emperor Tenji, who ruled Japan in the middle of the 7th century, played a significant part in the country’s politics. Before he took control, emperors were just a “symbol” of Japan, taking care of religious roles only; the real power was obtained by a clan called Soga (蘇我氏), and they were tyrants. Emperor Tenji destroyed them, the leader of clan was killed with his own hand.

…This is the history all the Japanese people and historians believed until very recently. Clan Soga needed to be villains no matter what, because an emperor cannot be a murderer. Even though Soga clan ruled Japan very well, more so than the members of the Imperial family, their politics needed to be described as tyrannical. If not, there would be no good logical explanation why the clan was destroyed and the Imperial family took their place.

There is almost no historical material that supports the suggestion that the Clan Soga were good people and that the true villains were the Imperial family, but archaeological evidence shows that Soga members were trying to protect Japan from threats from abroad. Many facts amongst the archaeology and other small pieces of evidence are contradictory, and the “true history” book might present completely different narratives. However we need to applaud the compilers of Nihon-Shoki for doing a wonderful job because they succeeded in brainwashing Japanese people until the end of the 20th century.

Manyōshū

Two out of the three oldest books were histories, whereas Manjōshū is a collection of approximately 4500 waka; traditional Japanese poetry. Manyōshū shows the joy, affection, sadness and sorrow of ancient people, not only the ones with authority but also commoners. Half of waka’s authors are unknown.

The very first waka was written by Emperor Yūryaku around the middle of the 5th century. In the poem, he speaks to a young woman in the field, asking her name. I find it very romantic. They are not categorised as romance, but there are a lot of romance-related waka in Manyōshū, and through them we can see the ancient romance protocol and marriage system. The latter are incredibly different to those we see in modern times, although the heartache caused by them is the same.

History told by Manyōshū

Even though Manyōshū was not intended as a historical record, we can use it to “fact check” for Kiki. For instance, there are multiple waka by Emperor Tenji, whom I referred to earlier, and one of them is:

香具山と 耳梨山と あひし時

立ちて見に来し 印南国原

Mount Kagu strove with Mount Miminashi, for the love of Mount Unebi. Such is love since the age of the gods; As it was thus in the early days, So people strive for spouses even now.

There are three mountains where the Imperial court was at that time. Emperor Tenji wrote about the mythical relationship of mountains, but there is a possibility that he was not trying to talk about the legend.

Emperor Tenji had a little brother, and tradition has it that his wife was a very beautiful, talented poet. She, Nukata-no-ōkimi, is one of the leading poets in Manyōshū. According to the multiple waka written by them, it is likely that the Emperor made his little brother divorce so that he could take his brother’s lovely wife as his own. From waka, we can make assumptions as to when the love triangle started and how it went.

After the death of Emperor Tenji, his little brother won the throne after the largest civil war in ancient Japan, and destroyed Tenji’s descendants. The feud between the brothers might have started with romance.

Waka are great historical material

The most common waka is formed with 31 syllables, 5-7-5-7-7. There is not enough space to tell all of the details in one waka, so waka are very implicit, giving us considerable room as to how we interpret them. Thus, people who cannot speak up publicly could express their hidden thoughts implicitly in 31 sounds.

There are many waka in Nihon-Shoki as well, and they are also useful for fact checking because waka could escape the manipulation of the compilers of Nihon-Shoki. Based on a waka by an Emperor called Kōtoku, some historians suggest that his queen had an affair with Emperor Tenji, who happened to be Tenji’s real sister.

Apparently craving a strong position, Tenji took power and authority from Emperor Kōtoku, as well as his wife, and later became an emperor. Because of Tenji’s treatment, Emperor Kōtoku became sick and mad, dying soon after.

Emperor Tenji seems quite an aggressive and unique character. But it is impossible to comprehend these characteristics from Nihon-Shoki alone, which just tells how wonderful he was as a politician.

Nihon-Shoki is thought to have been finished in 720, which means the compilers were dealing with Tenji, who lived in the mid 7th century; they were writing about events as far distant as the Second World War is from the present day. Imagine how difficult it was, even 9/11 was described differently, depending on witness or the record, and it was just two decades ago.

Additionally, for the ancient writers, there were no recorders or videos; even paper was too expensive for rich people. Thus, when it comes to the history of the 4th or 5th century, we should not rely on most of the things Kiki tells us. There are surely many unintended mistakes and typos in Kiki as well as the intended ones. It makes history harder to comprehend and interpret, but it also makes the journey of studying very exciting.

- At that time there was no country called “Japan” or “Nihon”, it was called “wa (倭)” by foreign countries. One tribe called themselves “Yamato(大和)”, and there were other kingdoms and tribes. In history books written in Japanese we use these names, but here, since it is confusing in English, I will write “Japan” when I mention the whole entity constituting the Japanese islands, unless I need to refer to a specific tribe.

- The kanji for “ki” are different in Kojiki (古事記) and Nihon-Shoki (日本書紀), so when we see “紀”, it means Nihon-Shoki. This difference between the characters for “ki” is a typical Kanji question in middle school history classes in Japan.

- When history is written chronologically it is called “hennen-tai” (編年体), and it was one of the ways to compile history in East Asia. Nihon-shoki is hennen-tai; Kiden-tai (紀伝体) is another form that focuses on the people involved in historical events. Kojiki is more like Kiden-tai, although it does not follow all the Kiden-tai rules.