by

Lina Japanese Writer/Translator

by

Lina Japanese Writer/Translator

Mount Fuji, Japan’s tallest peak, is not just a mountain boasting a height of 3,776 meters. Its grandeur and majestic presence, with a broad base rooted deeply in the earth, have made it a frequent subject in literature and art from ancient times to the present. Mount Fuji is also an active volcano, continuing its geological activities even today.

Straddling the border between Shizuoka and Yamanashi Prefectures in central Honshu, Mount Fuji has been an object of reverence in Japanese spirituality since ancient times. Today, it is a popular destination for climbers. The phenomena of ‘Diamond Fuji’ and ‘Red Fuji’ are especially noted for their beauty, often listed as sights to see at least once in a lifetime.

There are records indicating that in ancient times, Fuji was written as “不二山” (Fujisan), interpreted to mean “a peerless mountain”. Additionally, the name Fuji is thought to resonate with the word for immortality, “不死” (fushi). This connection is highlighted in Japan’s oldest narrative, “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” where an emperor burns the elixir of immortality given by Princess Kaguya at Mount Fuji.

Mountain Worship: Fuji as a Sacred Entity

Two-thirds of Japan’s landmass is covered in forests. Despite having a population of 125 million, the habitable land in Japan, where people can live, amounts to only about 30% of the total land area.

Compared to other countries, such as the UK, which has two-thirds the land area of Japan, the UK has twice the habitable land proportion. Consequently, Japanese people have historically settled in the limited plains and basins that can support urban life, such as in Tokyo and Osaka.

For the Japanese, who have lived in a land surrounded by mountains, these natural formations have always been objects of worship.

Mountain worship predates the formal systems of Buddhism and Shintoism, rooted in animistic beliefs. Mountains were revered both as providers of food and necessities of life and feared as harbingers of disasters. Beliefs like “If you desecrate the mountain, calamity will come” and “If the mountain is pleased, there will be a bountiful harvest” have been ingrained in the Japanese psyche. Such admiration and fear of mountains evolved into a form of religious worship.

Mount Fuji itself was revered as a ‘divine entity’ in this belief system. While mountain worship may not be formally recognized as a religion today, many Japanese still visit Mount Fuji and other mountains as ‘power spots.’

Mount Fuji in Literature and Art

As an object of worship, Mount Fuji has frequently appeared as a theme in literature and art.

For example, the famous poet Yamabe no Akahito penned, “When I came out to Tago’s coast, I saw, amid the snows, Mount Fuji rise in lofty grace.” This verse, depicting the snow-capped Mount Fuji, is renowned and included in the classic anthology of Japanese poetry, the “Hyakunin Isshu.”

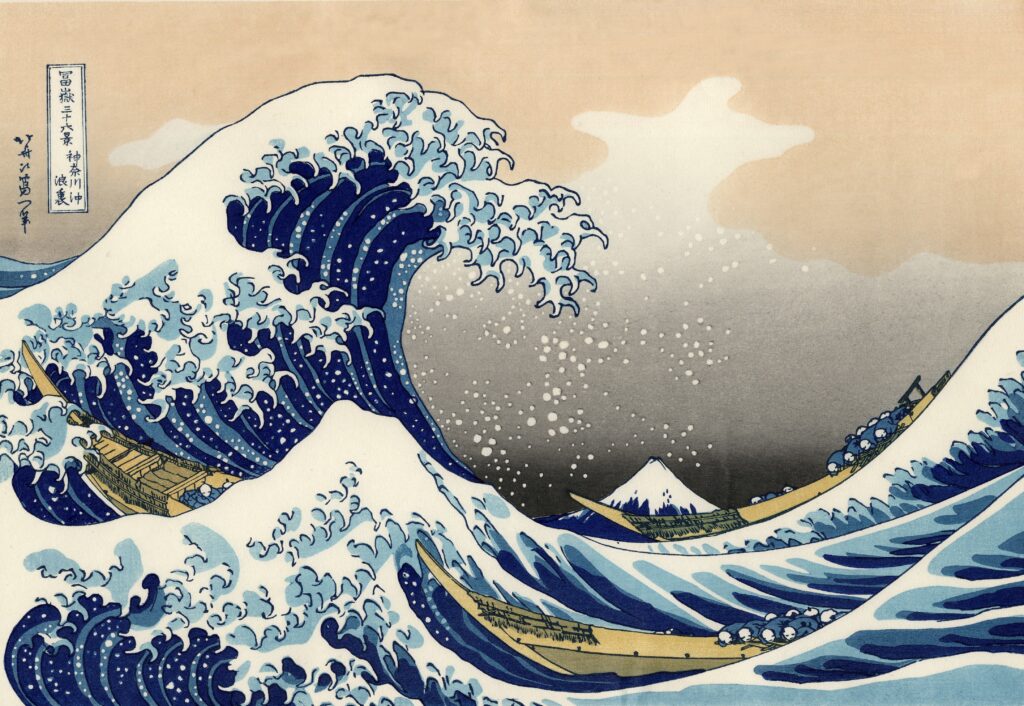

Moreover, Mount Fuji has been a recurrent subject in Ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

Katsushika Hokusai’s “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” is particularly well-known. This series consists of 36 pieces depicting Mount Fuji from various locations, seasons, and weather conditions. “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” from this series is celebrated worldwide as an iconic representation of Japan.

Furthermore, Hokusai depicted the ‘Red Fuji’ in his work ‘Fine Wind, Clear Morning.’ Red Fuji refers to a phenomenon where, during the late summer to early autumn mornings, the sunrise’s reflection on clouds or mist gives Mount Fuji a reddish hue. This striking appearance of Mount Fuji has captivated numerous photographers and painters.

Additionally, the rarer ‘Diamond Fuji’ is also popular. Diamond Fuji is a scenic view where the sun aligns with Mount Fuji, creating an illusion of a sparkling diamond at the mountain’s peak. This spectacle can be witnessed only twice a year, for a few days each time, and under specific locations and meteorological conditions.

The “Mountain of Immortality” in The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

Mount Fuji features in Japan’s oldest narrative, “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.”

This story revolves around Princess Kaguya, famed for her exquisite beauty, who receives marriage proposals from various nobles, including the Emperor. However, Kaguya is not a human but a lunar being and eventually returns to the moon. As a parting gift, she leaves the Emperor an elixir of immortality. The Emperor, stating that living forever without Kaguya would be meaningless, orders the elixir to be burnt at the place on Earth closest to Kaguya, which was the moon.

Accordingly, the elixir of immortality was burned at the location deemed closest to the moon, leading to the naming of the mountain as the “Mountain of Immortality” – Mount Fuji. The story concludes with the eternal ascent of the smoke from the elixir into the sky.

This narrative element suggests that at the time of writing “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” smoke was rising from the summit of Mount Fuji, indicating its volcanic activity.

Mount Fuji as a Volcano

The current form of Mount Fuji is believed to have been shaped by four stages of volcanic activity.

The initial formation of the mountain occurred about 700,000 years ago through two volcanic activities. Further eruptions from approximately 80,000 to 15,000 years ago deposited volcanic ash, allowing the mountain to grow to just under 3,000 meters in height. Subsequently, about 10,000 years ago, a series of events including lava flows, pyroclastic flows, and landslides led to its current appearance.

The most recent significant eruption, known as the Hōei Eruption, occurred around 300 years ago in 1707. The volcanic activity, which lasted for about two weeks, resulted in widespread ashfall. This ashfall caused the collapse or burning of houses and storehouses, exhausted food supplies, and rendered fields unfit for cultivation. Water supply channels were also buried, leading to severe famines in the affected areas.

Mount Fuji remains an active volcano, and an eruption similar to the Hōei Eruption could occur at any time.

In the event of an eruption of similar magnitude to the Hōei Eruption, it is estimated that up to approximately 750,000 people might need to evacuate due to lava flows. Around 470,000 people could be affected by ashfall exceeding 30 cm in thickness. Additionally, it’s predicted that volcanic ash, carried by the prevailing westerly winds, could deposit approximately 2 cm of ash across the entire Tokyo area and parts of Chiba Prefecture.

Climbing Japan’s Highest Mountain

Currently residing in the UK, I had planned to climb Mount Fuji before leaving Japan, wanting to experience something uniquely Japanese.

A two-day climb of Mount Fuji is advisable, with the highlight being the sunrise at the summit, known as ‘Goraikō,’ a favorite among climbers. Since its UNESCO World Heritage Site designation in 2013, the popularity of climbing Mount Fuji has soared.

You can reach the fifth station of Mount Fuji by bus or car, and the typical approach involves climbing to about the eighth station on the first day and staying overnight in a mountain hut. Climbers then ascend to the summit in the middle of the night to witness the Goraikō. This is the most popular way to enjoy climbing Mount Fuji.

Unless you are a professional mountaineer, climbing Mount Fuji should only be attempted during the official climbing season from June to September. Outside this period, the conditions become perilously wintery.

Even during the summer climbing season, temperatures near the summit can be winter-like, so adequate gear is essential. The risk of altitude sickness also suggests that those inexperienced in climbing might prefer joining a guided tour, especially important for children who may not effectively communicate their physical condition.

There are multiple routes to the summit of Fuji, each with varying degrees of difficulty. Those less confident in their physical fitness might choose beginner-friendly routes, and watching the Goraikō from a mountain hut before ascending to the summit after sunrise could be a safer option.

I enjoy mountaineering as a hobby, but I find the mountains in Japan to be deep and extremely dangerous. In 2022, there were 3,015 mountain accidents in Japan, with 1,306 injuries and 327 deaths or missing persons.

As mentioned, Japan is a land of mountains, offering endless hiking and climbing opportunities. However, this abundance also means it’s easy to become stranded on a casually chosen mountain.

For Mount Fuji, there are safety-conscious tours available, and it’s recommended for tourists to utilize these. Some tours provide not just guides and transportation but also include accommodations in mountain huts and climbing gear, making planning easier.

I had booked a tour and taken out insurance, looking forward to climbing Mount Fuji. However, the hectic preparations for moving to the UK consumed the time I had set aside for this adventure. This move was a significant step in my life that I didn’t want to jeopardize.

Admittedly, the thought of the Hōei Eruption briefly crossed my mind. The idea of dying in a Fuji eruption right before my long-awaited move to the UK seemed an unbearable irony, even though I knew it was an irrational fear.

The sudden eruption of Mount Ontake in central Japan in 2014, resulting in 58 deaths and 5 missing people, was a significant disaster. Many climbers, dressed lightly for what was considered an easy mountain, contributed to the scale of the tragedy.

Whenever I climb a sizeable mountain, I always take out insurance and either climb with a guide or experienced companions, or join a tour. While not rooted in religious mountain worship, one should never forget to respect and fear the mountains.

Reference

中村義裕『日本の伝統文化しきたり事典』

https://www.maff.go.jp/j/heya/kodomo_sodan/0105/19.html https://www.jice.or.jp/knowledge/japan/commentary06 https://ogurasansou.jp.net/columns/hyakunin/2017/10/17/230/ https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASR6H3CJFR6GUTIL02N.html#:~:text=2022%E5%B9%B4%E3%81%AE%E5%B1%B1%E5%B2%B3%E9%81%AD%E9%9B%A3,%E5%A2%97%E5%8A%A0%E3%81%AB%E8%BB%A2%E3%81%98%E3%81%A6%E3%81%84%E3%81%9F%E3%80%82 https://www.sankei.com/article/20150928-OKO2JAHEVFP6XE52HZZK5TGALM/